By TOM SHANAHAN

Bo Matthews paused as he recalled December 13, 1969, the day he and Wilbur Jackson were Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant’s first Black recruits to sign Southeastern Conference letters of intent. They knocked on history’s door.

Matthews grew up attending Black schools until his junior year (1968-69) at newly desegregated Butler High in Huntsville. Jackson’s lone season on a desegregated campus was his senior year (1969-70) at Carroll High in Ozark. They were examples of Black athletes suddenly on Bryant’s radar after Alabama’s school districts desegrated.

Matthews was a bruising fullback who proudly looked forward to his Alabama freshman year in the fall of 1970. Until, that is, Bryant called an August audible – eight months after he signed and mere days before 1970 fall camp opened and classes started.

Matthews learned through an assistant coach that Bryant wanted him to attend a junior college to improve his grades. Why Bryant – famously regarded as a man of character and builder of men – waited until August and tasked an assistant coach to inform an 18-year-old kid rather than his own face-to-face meeting remains a mystery to this day.

“I was sick,” Matthews said. “I told people Alabama was taking me and all of the sudden they don’t want to take me. I thought, ‘How am I going to face anybody? Why did they pick me in the first place?’ That stuck with me for a while.”

Only Jackson made it to the Tuscaloosa campus.

Over time Bryant’s omnipresent surrogates managed to cast him at the forefront of progress through the power of his legend, but a straightforward study of a 1960s timeline reveals he dragged his feet. Bryant, in fact, trailed his southern peers.

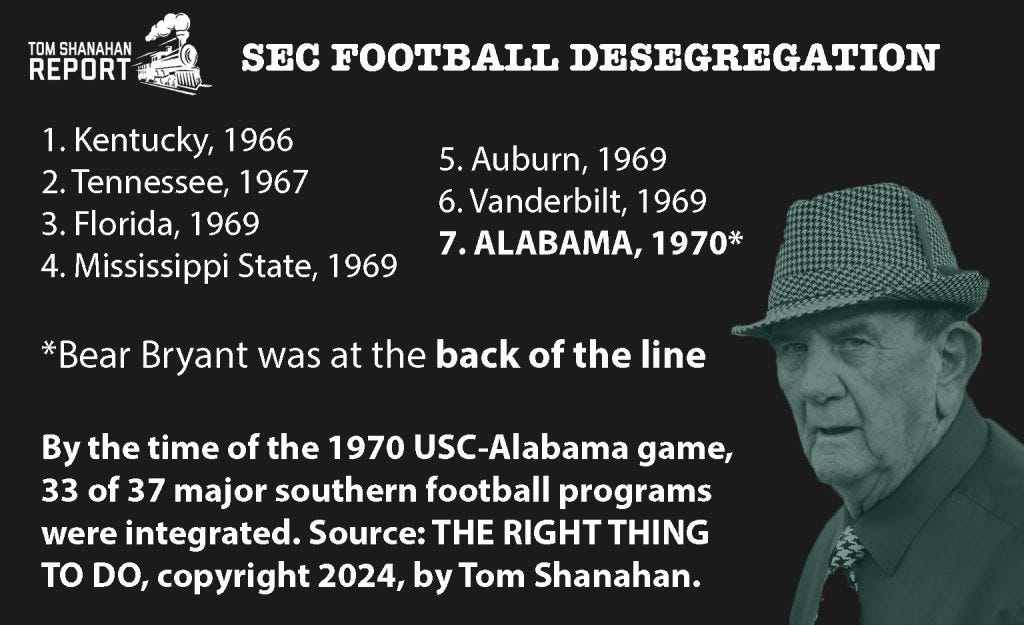

By the 1970 season, Alabama was the seventh of 10 SEC programs to integrate. And throughout the South, 33 of 37 major programs included Black players. The reality was Bryant played catchup.

The 1960s timeline more accurately reveals Matthews and Jackson metaphorically hoisted an antebellum figure onto their shoulders into the 20th century. But instead, with time, Matthews was written out of history.

If Bryant’s sycophants want to dispute Matthews’ version, they won’t find a Bryant explanation archived in newspaper stories or an account from Bryant in his 1974 book, “BEAR.”

Matthews’ embarrassment stayed with him for many years. That explains why he avoided discussing it long after his NFL career. But the pain has always gnawed at him.

“I could throw him under the bus,” Matthews said.

He paused instead.

Matthews continued the phone interview in an even-toned voice, but his caution was understandable. You don’t grow up in Alabama revering Bryant – despite the dichotomy of a Black kid cheering for all-White Alabama teams while living under Jim Crow subjugation — and then speak cavalierly of him.

Matthews said the only time he talked to Bryant throughout the recruiting process was a brief conversation at an event preceding the 1970 Alabama High School Athletic Association All-Star Game played on August 6 at Denny Stadium (now Bryant-Denny Stadium).

“Bryant was meeting all the players,” Matthews said. “When they got to me, they had to tell him, ‘This is your guy coming to Alabama.’ He didn’t say anything special to me. He kept shaking hands with others.”

Looking back on the moment, Matthews says he should have realized Bryant’s curt acknowledgement of him was “a red flag … that was the first time I saw him and the last time.”

Soon enough, the withdrawn scholarship bombshell dropped, but Matthews’ despair was short-lived.

He found football refuge in Colorado, thanks to Colorado assistant coach Steve Ortmayer, Colorado freshman coach Dan Stavely and a White businessman in Huntsville, Fred Singleton. They utilized Colorado’s Equal Opportunity Program that was a response to the Civil Rights movement’s agenda to level the playing field.

Matthews was a sophomore backup fullback for the Buffaloes in 1971 and a two-year starter, 1972 and 1973. The San Diego Chargers made him the second overall pick of the 1974 NFL draft. He played eight years in the NFL.

To bring Matthews’ Colorado EOP story full circle, he won a 1970 battle of opportunity, but he lost when he came down on the wrong side of Bryant hagiography and revisionist history.

Matthews’ brush with Alabama history can be found only through a bottomless well of untold stories spanning college football integration. His story is a fresh bucket of information from that otherwise untapped well.

WHY IT MATTERS

Bear Bryant hagiography and Black historiography tell conflicting versions of college football integration. The Grand Canyon-esque divide resulted from a journalism failure at both ends of a timeline.

In the 1960s, the sports media failed to properly credit many Black figures and moments courageously establishing milestones of progress. They’ve been overshadowed by myths falsely crediting Bear Bryant for the 1970 USC-Alabama game. At end of the timeline, the modern media remains subservient to Bryant’s legend.

— Bryant hagiography is an idealized biography that falsely claims he launched college football integration through orchestrating events around the USC-Alabama game played on September 12, 1970, at Legion Field in Birmingham.

Bryant, according to the narrative, scheduled USC as a game to lose. His strategy was to have his bigoted fanbase watch Black athletes run over his all-White team. The shock, according to the myth, was needed to gain permission to recruit Black players to remain competitive.

The perceived humor of the Black bully running over skinny White kids propelled the myth word of mouth into college football lore, but a simple calendar provides a glaring oversight to the myth:

Matthews and Jackson signed with Alabama a month before the game was scheduled and nine months prior to USC’s arrival. The game wasn’t scheduled until the NCAA voted in January 1970 to allow teams to schedule an 11th game.

Another curiosity was although the folklore wasn’t crafted and spread until the 1990s, it succeeded. The denouement of USC fullback Sam Cunningham’s dominant performance in the 42-21 victory fit snugly to be backed into the narrative with revisionist history.

— Black historiography includes many 1960s figures and moments who broke ground, but since the 1960s sports media avoided race, their milestones were ignored or overlooked by history.

In 1963 and 1964, the Atlantic Coast Conference broke ground. Maryland’s Darryl Hill was the South’s first Black player in a major conference in 1963 and a year later Wake Forest signed Bob Grant and Butch Henry among three Black players out of high school.

The dominos of “firsts” falling continued with Houston’s Warren McVea, the first Black player to sign at a major Texas school, 1964. Players from the two remaining major southern conferences signing were Southern Methodist’s Jerry LeVias in the Southwest Conference (1965) and Kentucky’s Nate Northington and Greg Page in the SEC (1966).

SEC progress continued as Tennessee signed Lester McClain in 1967. In the fall of 1969, conference rivals Auburn, Florida, Mississippi State and Vanderbilt included their first Black players.

But despite an indisputable 1960s timeline, both college football lore and the media continue to regurgitate Bryant mythology. Bryant’s legend defeats Black historiography by a shutout.

Revisionist history also overlooks USC wasn’t a model integrated program. The Trojans numbered only four Black starters in the 1970 game as a result of still shedding their years following the unwritten quota limiting Black athletes to a half-dozen or so.

USC numbered only five Black players on it 1962 national title team and only seven on its 1967 national championship roster despite a campus located in populous and diverse Los Angeles. It’s true USC numbered 18 Black players in 1970, but 11 arrived in 1969 or 1970 as junior college (nine) or four-year school transfers (two).

Lane Demas, an author of books on sports integration and a Central Michigan University history PH.d professor, says the Bryant-Cunningham myth also serves to discredit the Civil Rights movement.

“I still believe the Sam Cunningham story is not about celebrating Cunningham or USC, nor is it even about celebrating Bear Bryant or Alabama,” Demas said. “It’s one of the many White stories that emerge in the South during the 1970s that were meant to denigrate Martin Luther King, the countless marches and protests, the student sit-ins, and even the Civil Rights Act and the U.S. Supreme Court. The ultimate point of the Cunningham-Bryant myth was, ‘See, we didn’t need any of that.’”

THE ALABAMA STORY

Matthews’ rise to intersecting with history began with moving to Huntsville in the fall of 1968 to live with an older sister, Elizabeth. He left behind a troubled home life in the rural town of New Market, 17 miles north Huntsville. Bo’s father was a farmer who turned violent when he drank.

“He was bigger than me – and meaner,” Matthews said.

That’s a frightening image to ponder considering Bo’s body was ripped from granite. He tipped the scales as a 220-pounder in high school and played his NFL career as a chiseled 6-foot-3, 240-pounder.

Hollywood got it all wrong when it cast former NFL players Carl Weathers (Apollo Creed, Rocky movies) and Fred “The Hammer” Williamson (blaxploitation films) as intimidating Black men. They would have wilted standing next to Bo’s body.

The move to Huntsville provided Matthews with stability, although he was ineligible to play football upon enrolling as a junior at desegregated Butler High. When he gained eligibility as a senior, he quickly established himself. The first time he touched the ball in the 1969 season-opening win against Cullman, he broke off a 71-yard touchdown run.

Matthews was named first-team all-state, accepted an Alabama scholarship offer and earned an invitation to play in the state’s annual Alabama High School Athletic Association All-Star game.

That’s a triple crown. Bo Matthews’ life was opening up for him after growing up in a Jim Crow world.

Another hole in the Bryant 1970 USC-Alabama myth was Alabama’s high schools had desegregated by the late 1960s. Bryant’s 1968, 1969 and 1970 rosters were all-White, but high school teams throughout the state were integrated. The AHSAA and the governing body for the state’s Black schools had merged by the 1968-69 school year.

The 1970 USC game with Black athletes on the field was nothing new for Bryant’s younger players. The state’s growing acceptance of Black athletes by 1969 was reflected in newspaper coverage of Matthews and Jackson signing their letters of intent. There were no screaming headlines about breaking history or even references to race in the early paragraphs of stories. There was no labeling of Bryant as a crusader.

Tuscaloosa News Sports Editor Ed Darling’s story published on December 14, 1969, didn’t state until the 12th paragraph Matthews and Jackson were “the first Negroes to sign with the school.” He casually wrote “a bit of history was made.” The simple headline was, “16 Pick Alabama.”

Darling also mentioned Alabama’s first Black basketball player, Wendell Hudson, was on Alabama’s campus playing on the freshmen team (the NCAA didn’t permit varsity eligibility until 1972). Hudson signed his letter of intent in the 1968-69 high school year.

The signing day story in the December 14 edition of the Birmingham Post Herald that was written by Assistant Sports Editor Kirk McNair made no mention of race. He reported in the fifth paragraph a list of players who signed with Alabama. Matthews was at the beginning and Jackson at the end. The generic headline combined the Alabama and Auburn’s classes: “Long List Of Preppers Committed To Tide, Tigers.”

In the December 15 edition of the Tuscaloosa News, a story written by the Associated Press announced the 1969 4A All-State team. Matthews and Jackson were on first team and another African American who went on to play in the NFL, Ken Hutcherson of Anniston, was named honorable mention.

Anniston was the same town in 1961 where White supremacists firebombed a Greyhound Bus with the Freedom Riders aboard while the police looked the other way. The times were changing even in Anniston’s evil corner.

Hutcherson and John Stallworth of Tuscaloosa Druid also were chosen along with Matthews and Jackson to play in the AHSAA All-Star Game. All four Black all-stars went on to play in the NFL. Stallworth kept going all the way to four Super Bowl rings and the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The Birmingham News story on the 1970 AHSAAA All-Star game published on August 7 included a photo of Matthews running the football. So, whatever taboos southern papers previously followed against featuring Black athletes no longer mattered.

The website for the Alabama High School Football Historical Society includes a summary of the 1970 all-star game results and rosters that noted the players’ college choices. Matthews and Jackson to this day are both listed as committed to Alabama.

THE COLORADO DETOUR

Matthews, upon losing his scholarship, sought advice from Butler coach John Meadows, an Alabama high school coaching legend who was White.

In the pre-Internet era, a high school coach was the most influential figure for a player choosing a college destination. Meadows had encouraged Matthews to break ground by committing to Alabama. But when the scholarship was withdrawn, Meadows advised against Bryant’s instructions to attend junior college.

“He told me I could get hurt at a junior college and then where would I be,” Matthews said. “He said if I had other options, I should consider them.”

Matthews’ offers were largely limited to Historically Black Colleges and Universities, although Jacksonville State, a predominantly White campus in Jacksonville, Alabama, recruited Matthews. A Penn State alumnus living in Huntsville often spoke with Matthews about the school’s program led by its then-fourth-year coach, Joe Paterno.

“I knew Penn State had Black players,” said Matthews, “but nothing developed with me taking a recruiting trip.”

In a Tuscaloosa News story dated August 7, 1970, Charles Land wrote a brief note at the bottom of a story about the Alabama varsity. He wrote Matthews wasn’t playing for Alabama due to academics and planned to enter Jacksonville State. Did Bryant plant that tidbit? Land’s reporting, without noting attribution, apparently was unaware Colorado’s recruiters had reentered the picture.

The sudden turn-of-events was detailed a year later in a 1971 story written by Dan Creedon in the Boulder (Colorado) Daily Camera. Creedon’s thorough reporting has stood the test of time, filling in the unexplained gaps in memories and in the narratives slanted to favor Bryant.

His 1971 story explained Ortmayer and Stavely visited with Matthews the week of the 1969 Liberty Bowl in Memphis. They drove across the Tennessee-Alabama border to Huntsville. Ortmayer was then a 25-year-old defensive line coach.

Creedon quoted Ortmayer: “I made quite a few calls ahead of the ’69 Liberty Bowl checking on the top players in the area (and mid-South). And at least two high school coaches told me Bo was the best player ever to come out of northern Alabama. I visited him once before the game and coach Stavely went over to see him, too.”

Coincidentally, the Liberty Bowl was played on December 13, the same day Matthews signed his SEC letter of intent. In other words, Matthews had yet to officially commit when the CU coaches visited him, but Colorado’s coaches invited Matthews on a recruiting trip to Boulder.

Ortmayer and Stavely explained to Mathews as an NCAA academic non-predictor he could be admitted through the school’s Equal Opportunity Program, but he was ineligible to receive an athletic scholarship or permitted to play or practice on the freshmen team.

The financial hurdle was cleared when the owner of Singleton’s, a Huntsville sporting goods store, offered to pay Matthews’ freshman year college expenses. Matthews had worked a part-time job for the owner, Fred Singleton.

“I didn’t have any money when I got to Huntsville, and I worked at his store after school for about a year and a half,” Matthews said. “He was a good man.”

Creedon’s story stated Matthews enrolled just two days before the start of 1970 fall classes. Matthews “C average” as a freshman gained eligibility for a scholarship as a sophomore.

Matthews was backup fullback on the 1971 team that finished 10-2 and ranked No. 3 in the nation. The Buffaloes’ only losses were to their Big Eight Conference rivals, No. 1 Nebraska and No. 2 Oklahoma.

With Matthews a junior in the 1972 starting lineup, Colorado finished 8-4 and ranked No. 16. The Buffaloes earned a bid against Auburn in the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida. That was a news hook worthy of a hometown kid story in the December 14, 1972, edition of Huntsville Times. Assistant sports editor John Pruett’s article quoted Matthews, Meadows and Nebraska All-American defensive end Willie Harper.

“He’s the best fullback I’ve ever seen,” Harper said. “Nobody goes over big Bo.”

In the same article, Pruett recycled a Meadows quote from one of his 1969 Butler preseason stories. Meadows’ comment sounded presciently like a 1980s Nike Bo Jackson commercial.

“We’re going to have a good fullback,” said Meadows. “Not many people know about him yet, but they’ll find out pretty soon.

“They’ll know all about Bo.”

THE URBAN LEGENDS

Not surprisingly, the urban legends explaining Matthews’ journey to Colorado leaned to Bryant folklore. They portrayed Matthews as an enigma and Bryant as a shining White knight.

Here are three commonly told stories:

— 1) Matthews changed his commitment from Alabama to Colorado after he met the Buffaloes’ players at the Liberty Bowl played against Alabama. Colorado’s roster included seven African Americans in the game the Buffaloes won, 47-33.

The tale was regurgitated in a 2013 story by Kevin Scarbinsky of Al.com (an Alabama newspaper group). His article’s overall theme defended Bryant for waiting until 1970 to integrate. He vaguely referenced Matthews changed his commitment upon meeting Colorado’s players.

In 2016, Denver Post columnist Woody Paige wrote a similar story claiming Matthews’s time with the Buffaloes flipped his commitment.

Both accounts make Bryant sound like an innocent victim of Matthews’ whims.

Matthews’ account: “I didn’t go to the game, and I wasn’t in Memphis.”

— 2) In 2024, Mark Inabinett wrote a story in Al.com about the NFL draft that highlighted Alabama high school alums selected in past years. The story noted Matthews was the second overall pick in 1974. However, Inabinett’s story also mentioned Matthews wasn’t admitted to Alabama for poor grades.

Matthews’ account: “Colorado had a program for minorities, but Alabama didn’t offer one to me. They only told me they wanted me to go to a junior college.”

CU’s Equal Opportunity Program was typical among schools establishing open doors in the wake of the 1960s Civil Rights movement. A story blaming Matthews for his grades conveniently excuses Bryant from any fault, but it also ignores many coaches – including Bryant — skirted sub-par grades to admit a player they wanted.

Alabama legendary quarterback Joe Namath was admitted after he was denied admission at schools during the recruiting process. Maryland gave Namath one more chance to pass the board exams on the eve of fall camp, in 1961. He failed. And after Maryland coach Tom Nugent informed Bryant that Namath was available, Namath was admitted to Alabama overnight.

Alabama was then and now a football factory, and Bryant’s grand stature was such that he didn’t have a boss. If anyone thinks Namath in 1961 was the only recruit Bryant pushed through the admissions office, they don’t know the definition of a college football factory.

Nevertheless, a basic curiosity remains to the overall story: Colorado accepted a player Alabama rejected, even though Colorado was a higher ranked academic institution then and now. This wasn’t Colorado vs. Harvard.

— 3) A Colorado urban legend claims Bryant called Colorado coach Eddie Crowder when he learned Matthews was uncomfortable with Alabama’s racial climate. He asked Crowder to take Matthews. The tale conveniently paints Bryant as a benevolent segregationist.

Matthews’ account: Matthews said he didn’t express second thoughts about attending Alabama to Bryant. His only conversation with Bryant, after all, was that drive-by hello at the pre-Alabama All-Star Game event.

Another problem with the narrative is Bryant folklore pushes the claim Bryant sent Black players from the South to his friend, Michigan State coach Duffy Daugherty. There are no similar stories about Eddie Crowder.

Bryant was a master manipulator of the media who never missed a chance to plant a seed with the media. The myths Bryant sent Daugherty players began with a vague reference from the Bear in a 1980 Time Magazine story. None of Daugherty’s Underground Railroad passengers have told a Bear Bryant backstory, but the unsubstantiated claim Bryant sent Daugherty players has been extrapolated.

Crowder was Colorado’s head coach through 1973 and continued in the athletic administrative office until 1984, but he hasn’t been quoted about a call from Bryant to him. Bryant made no mention of Matthews in any form in his 1974 book written with John Underwood, “BEAR.”

Stavely died in 2003, Crowder in 2008, Creedon in 2013 and Ortmayer in 2021. Bryant died in 1983.

THE COLD, HARD FACTS

The primary myth used to excuse Bryant waiting until 1970 was racist Alabama Gov. George Wallace wouldn’t allow him to recruit Black players. But Wallace wasn’t in office from 1967 to 1971, and Auburn and coach Ralph “Shug” Jordan signed his first Black player one year prior to Bryant. Nobody first Jordan.

Auburn, of course, is Alabama’s in-state SEC rival. Jordan signed James Owens as Auburn’s first Black player, in his 1969 class. Owens was a senior in the fall of 1968 at desegregated Fairfield High near Birmingham.

He played in the 1969 AHSAA All-Star Game a year before Matthews and Jackson were named to participate.

Alabama and Troy State (now Troy) were the last two state college football programs to integrate. Alabama’s campus had been desegregated since 1963. In addition to Auburn, Jacksonville State, North Alabama and West Alabama were integrated.

Two transformative moments long before 1970 involve Michigan State’s 1964 and 1966 teams. Daugherty, the Spartans’ College Football Hall of Fame coach, assembled the game’s first fully integrated rosters.

— On September 26, 1964, Michigan State was the college football’s first fully integrated team to play in the South in a game at North Carolina’s Kenan Stadium.

— On November 19, 1966, the Game of the Century matched Michigan State against Notre Dame at Spartan Stadium. The Spartans lined up 20 Black players, 11 Black starters, two Black team captains, College Football Hall of Famers George Webster and Clinton Jones, and the South’s first Black quarterback to win a national title, Jimmy Raye of Fayetteville, N.C. Notre Dame had one Black player, Alan Page.

And there’s more progress to note prior to 1970.

College football lore overlooked when USC routed Alabama 42-21, it wasn’t anything new. It followed two games played in 1969 when integrated opponents rolled up 40-plus points on the Crimson Tide. In other words, there was no “shock” among Alabama fans by the time USC totaled 42.

— On October 18, 1969, Tennessee was in its third year as an integrated program when the Volunteers routed all-White Alabama 41-14 in a game at Legion Field. Jackie Walker, the SEC’s first Black All-American as a linebacker, intercepted a pass he returned for a touchdown and a 21-0 first-quarter lead. By contrast, the USC-Alabama game was still a one-score game, 15-7, late in the second quarter.

— On December 13, 1969, two months after Tennessee routed Alabama, Colorado beat the Crimson Tide 47-33 in the Liberty Bowl. Another aspect of the game ignored in the media was Colorado’s support for its seven Black teammates. They recognized the environment for their Black teammates playing in a city where Martin Luthe King was assassinated a year earlier.

During the pre-game ritual of team captains meeting at midfield for the coin flip, Alabama sent 40 players lined up against Colorado’s tri-captains, Bill Collins, an African American, and two White players, Bob Anderson and Mike Pruett. But when Anderson and Pruett recognized what was happening, they wanted to make a statement. They stood back at the hashmark and told Collins to step forward alone to represent the Buffaloes.

At halftime in the locker room, Colorado defensive lineman Bill Brundige called attention to Alabama’s fans yelling racial slurs and the N-word.

“Did you hear what they were calling our Black brothers?” he shouted.

The team used it as a rallying cry. Brundig finished with five of the team’s eight sacks as the Buffaloes outscored Alabama in the fourth quarter, 16-0, with two touchdowns and a safety.

— On September 12, 1970 – which was the same day USC and Alabama played — integrated Stanford was a second Pac-8 team winning on that day at a venerated southern stadium. Stanford defeated Arkansas at War Memorial Stadium in Little Rock. Hillary Shockley, a Black fullback, was the star of the game. He led Stanford with 149 yards and three touchdowns, but the 1970 USC-Alabama myth lauds Cunningham as solitary Black figure venturing into the South.

Stanford-Arkansas was ABC-TV’s national game of the week. USC-Alabama was limited to the schools’ radio networks.

— In another southern opener on September 12, 1970, African American quarterback Eddie McAshan led Georgia Tech past integrated South Carolina at Grant Field in Atlanta.

College football integration was a fait accompli by 1970.

The myths about the 1970 USC-Alabama game weren’t crafted and spread until two decades later. That lack of awareness of so many 1960s events opened the door to Bryant myths filling the void.

Myths develop as simple tales dubiously lacking proper research, according to Ken Burns, the award-winning historian and documentary filmmaker.

“We tend to resort to conventional, superficial understandings, tying things up to nice bows,” Burns said.

Simple tales continue to be told in misleading films: HBO’s “Breaking the Huddle,” 2008; Showtime’s “Against the Tide,” 2013; and ESPN films, 2019 and 2020.

THE BOTTOM LINE

In Alabama’s 1971 season, Jackson joined the varsity as a sophomore along with junior John Mitchell, a transfer from Eastern Arizona Junior College by way of Mobile, Alabama.

Mitchell was originally committed to USC until Trojans coach John McKay made the mistake of informing Bryant he found a player from his backyard. McKay told the story with ironic humor in his 1974 book, “McKay: A Coach’s Story.”

Bryant promptly instructed his assistants to locate Mitchell. They flipped him to Alabama.

In other words, Bryant mythology portrays him as an integration crusader, even though half of the two Black players on his 1971 varsity roster arrived by accident. This story contradicts folklore from Bryant’s sycophants he searched far and wide for a Black player as if he was Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey searching for Jackie Robinson.

In 2022, Alabama honored Jackson and Mitchell as its first two Black varsity football players with a plaque outside Bryant-Denny Stadium. But when an Associated Press story quoted then-Alabama coach Nick Saban praising Bryant as an integration leader, Saban exposed himself as uniformed or naïve.

His players couldn’t put one over him in his long career, but Alabama’s Bryant folklore has misled him. In praising Jackson and Mitchell as “people who did something that nobody else was really willing to do,” he added, “I think Coach Bryant should be commended for what he did to make that happen.”

Saban’s praise ignored the 1960s trailblazing players and coaches at other southern schools who opened their doors. They deserve credit for Alabama getting on board in the 1970s, but there’s more to question about Bryant’s commitment to progress.

In that same 1970 season, Condredge Holloway, a Black quarterback at integrated Huntsville Lee, was highly recruited. Bryant told Holloway that Alabama wasn’t ready for a Black quarterback, even though Alabama lost to USC and its Black quarterback, Jimmy Jones. Holloway went to Tennessee in the 1971 recruiting class as a three-year starter.

Was Bryant a leader or stuck in his ways following stereotypes?

Matthews, now 73, settled in the Denver area after his NFL days. In a 2016 Denver Post story, Matthews was recognized as one of “12 men of distinction” for having founded the Bo Matthews Center for Excellence, a non-profit for underserved communities. Matthews, who later returned to Huntsville, opened a similar center to serve his hometown.

With the 2025 NFL draft upon us and Heisman Trophy winner Travis Hunter of Colorado possibly the first pick, Matthews’ stature as the Buffaloes’ highest draft pick at No. 2 overall in 1974 will likely be cited often. But don’t count on the national media telling Matthews’ full story. That requires countering Bryant mythology, a road a compliant media avoids traveling down.

College football lore doesn’t know Bo the way it should know Bo.

-3